Electric displacement field

In physics, the electric displacement field, denoted as  , is a vector field that appears in Maxwell's equations. It accounts for the effects of free charges within materials. "D" stands for "displacement," as in the related concept of displacement current in dielectrics. In free space, the electric displacement field is equivalent to flux density, a concept that lends understanding to Gauss's law.

, is a vector field that appears in Maxwell's equations. It accounts for the effects of free charges within materials. "D" stands for "displacement," as in the related concept of displacement current in dielectrics. In free space, the electric displacement field is equivalent to flux density, a concept that lends understanding to Gauss's law.

Contents |

Definition

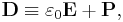

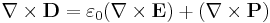

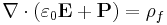

In a dielectric material the presence of an electric field E causes the bound charges in the material (atomic nuclei and their electrons) to slightly separate, inducing a local electric dipole moment. The electric displacement field D is defined as

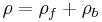

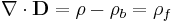

where  is the vacuum permittivity (also called permittivity of free space), and P is the (macroscopic) density of the permanent and induced electric dipole moments in the material, called the polarization density. Separating the total volume charge density into free and bound charges:

is the vacuum permittivity (also called permittivity of free space), and P is the (macroscopic) density of the permanent and induced electric dipole moments in the material, called the polarization density. Separating the total volume charge density into free and bound charges:

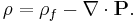

the density can be rewritten as a function of the polarization P:

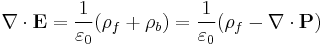

P is a vector field whose divergence yields the density of bound charges  in the material. The electric field satisfies the equation:

in the material. The electric field satisfies the equation:

and hence

.

.

The displacement field therefore satisfies Gauss's law in a dielectric:

.

.

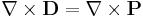

D is not determined exclusively by the free charge. Consider the relationship:

Which, by the fact that E has a curl of zero in electrostatic situations, evaluates to:

Which can be immediately seen in the case of some object with a "frozen in" polarization like a bar electret, the electric analogue to a bar magnet. There is no free charge in such a material, but the inherent polarization gives rise to an electric field. If the wayward student were to assume the D field were entirely determined by the free charge, he or she would immediately conclude the electric field were zero in such a material, but this is patently not true. The electric field can be properly determined by using the above relation along with other boundary conditions on the polarization density yielding the bound charges, which will, in turn, yield the electric field.

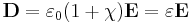

In a linear, homogeneous, isotropic dielectric with instantaneous response to changes in the electric field, P depends linearly on the electric field,

where the constant of proportionality  is called the electric susceptibility of the material. Thus

is called the electric susceptibility of the material. Thus

where  is the permittivity, and

is the permittivity, and  the relative permittivity of the material.

the relative permittivity of the material.

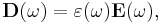

In linear, homogeneous, isotropic media  is a constant. However, in linear anisotropic media it is a matrix, and in nonhomogeneous media it is a function of position inside the medium. It may also depend upon the electric field (nonlinear materials) and have a time dependent response. Explicit time dependence can arise if the materials are physically moving or changing in time (e.g. reflections off a moving interface give rise to Doppler shifts). A different form of time dependence can arise in a time-invariant medium, in that there can be a time delay between the imposition of the electric field and the resulting polarization of the material. In this case, P is a convolution of the impulse response susceptibility χ and the electric field E. Such a convolution takes on a simpler form in the frequency domain—by Fourier transforming the relationship and applying the convolution theorem, one obtains the following relation for a linear time-invariant medium:

is a constant. However, in linear anisotropic media it is a matrix, and in nonhomogeneous media it is a function of position inside the medium. It may also depend upon the electric field (nonlinear materials) and have a time dependent response. Explicit time dependence can arise if the materials are physically moving or changing in time (e.g. reflections off a moving interface give rise to Doppler shifts). A different form of time dependence can arise in a time-invariant medium, in that there can be a time delay between the imposition of the electric field and the resulting polarization of the material. In this case, P is a convolution of the impulse response susceptibility χ and the electric field E. Such a convolution takes on a simpler form in the frequency domain—by Fourier transforming the relationship and applying the convolution theorem, one obtains the following relation for a linear time-invariant medium:

where  is frequency of the applied field (e.g. in radian/s). The constraint of causality leads to the Kramers–Kronig relations, which place limitations upon the form of the frequency dependence. The phenomenon of a frequency-dependent permittivity is an example of material dispersion. In fact, all physical materials have some material dispersion because they cannot respond instantaneously to applied fields, but for many problems (those concerned with a narrow enough bandwidth) the frequency-dependence of

is frequency of the applied field (e.g. in radian/s). The constraint of causality leads to the Kramers–Kronig relations, which place limitations upon the form of the frequency dependence. The phenomenon of a frequency-dependent permittivity is an example of material dispersion. In fact, all physical materials have some material dispersion because they cannot respond instantaneously to applied fields, but for many problems (those concerned with a narrow enough bandwidth) the frequency-dependence of  ; can be neglected.

; can be neglected.

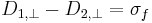

At a boundary,  , where

, where  is the free charge density.[1]

is the free charge density.[1]

Units

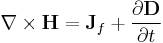

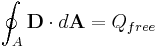

In the standard SI system of units, D is measured in coulombs per square meter (C/m2). This choice of units (together with measuring the magnetizing field H in amperes per meter (A/m)) is designed to absorb the electric and magnetic constants in the Maxwell's equations expressed in terms of free charge and current, and results in very simple forms for Gauss's law and the Ampère-Maxwell equation:

Choice of units has differed in history, for example in the Gaussian CGS system of units the unit of charge is defined so that E and D are expressed in the same units.

Example: Displacement field in a capacitor

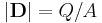

Consider an infinite parallel plate capacitor placed in space (or in a medium) with no free charges present except on the capacitor. In SI units, the charge density on the plates is equal to the value of the D field between the plates. This follows directly from Gauss's law, by integrating over a small rectangular pillbox straddling one plate of the capacitor:

On the sides of the pillbox,  is perpendicular to the field, so that part of the integral is zero, leaving, for the space inside the capacitor where the fields of the two plates add

is perpendicular to the field, so that part of the integral is zero, leaving, for the space inside the capacitor where the fields of the two plates add

,

,

where  is surface area of the top face of the small rectangular pillbox and

is surface area of the top face of the small rectangular pillbox and  is just the free surface charge density on the positive plate. Outside the capacitor, the fields of the two plates cancel each other and

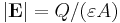

is just the free surface charge density on the positive plate. Outside the capacitor, the fields of the two plates cancel each other and  If the space between the capacitor plates is filled with a linear homogeneous isotropic dielectric with permittivity

If the space between the capacitor plates is filled with a linear homogeneous isotropic dielectric with permittivity  the electric field between the plates is constant:

the electric field between the plates is constant:  .

.

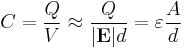

If the distance  between the plates of a finite parallel plate capacitor is much smaller than its lateral dimensions we can approximate it using the infinite case and obtain its capacitance as

between the plates of a finite parallel plate capacitor is much smaller than its lateral dimensions we can approximate it using the infinite case and obtain its capacitance as

.

.

See also

References

- ^ David Griffiths. Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd 1999 ed.).